Lag B’Omer and the Abbo Family Tradition of Safed

27 years before the first Zionist Congress in Basel;

50 years before the settling of the Jezreel Valley;

39 years before the founding of Degania and Kinneret;

12 years before the First Aliya and the founding of Gadera —

The Abbo family of Safed laid the foundations for Jewish agricultural settlement in the Galilee and the Hula Valley.

“No description of the settlements throughout the Galilee can survey the spread of Jewish settlement in that period without bringing in the name of the Abbo family, the Abbo brothers, the sons of Rabbi Shmuel Abbo,” writes Dr. Yoseph Sharvit, a researcher and lecturer in history at Ben-Gurion and Bar-Ilan Universities, in his comprehensive essay “France in the Galilee in the 19th Century,” and he devotes a sizeable chapter to the part of the Abbo consular dynasty in encouraging Jewish settlement.

“The historiography of settlement in the Land of Israel in the 19th century,” he points out, “has minimized or ignored the unique contribution of the Abbo family in purchasing lands that provided the basis for founding settlements in the 1880s in the Hula Rift, Upper Galilee, and Lower Galilee. The matter derives, inter alia, from the complex and ambivalent attitude of researchers regarding everything connected with the old Yishuv.

“Broader emphasis should be given to the contribution of the Abbo family, particularly in the preparatory stage of establishing the villages of the First Aliyah but also later,” Dr. Sharvit concludes

The Abbo Family Heritage

A five-generation tradition of parading the Torah scroll from the Abbo home in Safed to Meron on Lag B’Omer

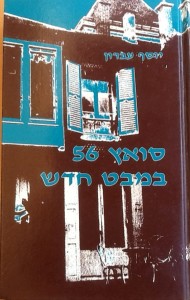

by Yoseph Abbo Evron

Lag B’Omer Eve, 2004

THE FIRST GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

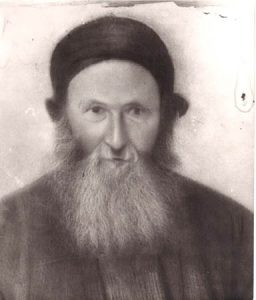

RABBI SHMUEL ABBO

The “Bnei Israel” affair – Descendants of Menashe in India

French Patronage over the Jews of Galilee

The Great Safed Earthquake

The Start of the Bar-Yochai Celebration and the Jewish settlement in Meron

THE SECOND GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RABBI YAAKOV CHAI ABBO

Redeeming Galilee Lands

The Founding of Rosh Pina

The Abbo Family Lays the Foundations for Settlement in Yesod HaMaalah and Mishmar HaYarden

Mei Merom – Predecessor of Yesud HaMaalah

Shoshanat HaYarden

THE THIRD CONSUL FROM THE ABBO FAMILY: RABBI YITZHAK MORDECHAI

THE THIRD GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

MEIR ABBO

The Abbo Home in Safed as a Shelter for Illegal Immigrants in the 1930s

The Saving of Mishmar HaYarden from the Corrupt Clerk of the Baron

THE FOURTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RAPHAEL ABBO

THE FIFTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

ZVI ABBO

YOSEPH ABBO EVRON

THE SIXTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RAPHAEL ABBO

On the festooned stage in the yard of the old Abbo house in Safed, the current representative of the family declares to the excited capacity crowd in an emotional voice: “I, Yoseph ben Raphael, ben Meir, ben Yaakov, ben Shmuel Abbo, fifth generation in the tradition, am honored to open the Lag B’Omer celebrations in Safed and Meron for this the one hundred seventy first year of the tradition and the

forty-sixth of the State of Israel.”

Yoseph Abbo Evron ceremonially opens the Lag B’Omer celebration of 1987. To his right, Safed mayor Zev Pearl, the French ambassador M. Alain Pierret and his wife.

With such words from the head of the Abbo family, the traditional celebrations in honor of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai have begun annually for five successive generations. Their origin was in the custom of bringing forth the Abbo family’s old Torah scroll, with much pomp and many spectators, from that same historical house in the Sephardic quarter of Safed, its foundations laid by the family forefathers at the start of the 19th century. On this day the town of Safed is wrapped in holiday. The neglected alleys of the Sephardic quarter awaken briefly from their yearlong slumber to the sound of merry shouts, and the Abbo home becomes once more a lighthouse sending its rays into the recesses of time.

The Torah parade on its way to Meron from the Abbo home

A generation ago, the Galilean writer and journalist Aharon Even-Chen, born in Rosh Pina, described the celebration in this way:

“The festivities in Safed and Meron were the ‘big attraction’ of our younger days, and we looked forward to them throughout those distant years of emptiness and boredom. Granted, the Purim carnival in Tel Aviv excited youthful imaginations in the Upper Galilee settlements, but Tel Aviv was far away, very far away, whereas we would ride to Safed and Meron on a horse or donkey. Of course we never missed the great zafa of Safed. The Sephardim used the Arabic name zafa (pronounced with the Z open and the F relaxed and rounded) for the procession that would gather heat and momentum as it made its way from the Abbo home up the alleys accompanied by a klezmer fanfare of clarinet, drum, and cymbal, the crowd fortified with enthusiasm and dripping with sweat, skipping and dancing with the Torah scroll and singing songs in praise of Bar Yochai in Hebrew, in Yiddish, and yes, in Arabic.

“‘Blessed are you, Bar Yochai! Blessed are you, Bar Yochai!’… We would descend into the Sephardic quarter, reach the Abbo family courtyard, and enter through its whitewashed arch. The courtyard held smells of jasmine flowers, broad beans, mint, and rue, and other fragrances of the east. The head of the family, Rabbi Meir Abbo, had inherited from his father and grandfather the privilege of taking the Torah scroll forth. Bright-eyed and swelling with pleasure, by the gate he greeted alike distinguished Jews and Arabs, officials and governors of the British mandate. The women would sprinkle the visitors with rosewater from oriental flasks, and some would break out in happy ululation.” (Ma’ariv — “Yamim v’Leilot / Days and Nights,” 3.VI.76)

Yoseph Abbo Evron, fifth generation of the tradition, 1987

Raphael Abbo, fourth generation of the tradition, 1963

How did the Abbo family come to be the only one in Israel continuing generation after generation, in its private capacity, a national public religious ceremony that over the years has become an integral part of Israel’s national folklore? That is the topic of this essay.

The name Abbo is drawn from the Hebrew initials of a phrase in Psalms 111:8: “formed in truth and uprightness.” The history of this special family — from which came rabbis and other great Jewish figures, redeemers and settlers of the land of the Galilee, and defenders of minority rights in the northern Land of Israel during Ottoman rule — makes it worthy of the name.

![]()

THE FIRST GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RABBI SHMUEL ABBO

The “Bnei Israel” affair — Descendants of Menashe in India

The first of the line in Israel was Rabbi Shmuel Abbo. He was born in Algeria in 1789. His father, Avraham, was not only a rabbi but also a merchant engaging in large-scale export. In 1817, Rabbi Shmuel arrived in Israel with his family, including his parents, and settled in Safed. He had three sons and two daughters — Avraham, Yitzhak, Yaakov, Sara, and Simcha. After a number of years, he traveled to India and received from David Sassoon a monopoly on trade in indigo in the vicinity of the Land of Israel. At Sassoon’s request, he stayed several years to organize the Jewish community and serve as its rabbi and teacher. In India, he first encountered the Bnei Israel community, who urged him to find them a solution enabling their recognition as full-fledged Jews. On returning to the Land of Israel, he raised the issue before the rabbis of Safed and Jerusalem, and in 1859 he returned to determine that the Bnei Israel were fulfilling all the religious requirements. In recognition of his work, the Jews of Bombay built a hostel named after Rabbi Shmuel Abbo.

When his son Avraham Chaim Abbo visited India in 1869, he found to his surprise that the Baghdadi Jews there continued to shun the Bnei Israel. When he protested to them, it was agreed that the rabbis of Safed should decide. Their answer was that the Bnei Israel were to be considered full-fledged Jews. The rabbis even wrote a detailed halachic ruling on the subject in the Hebrew year 5630 (1869–70) and the first signature on it was that of Rabbi Shmuel Abbo.

It bears noting that in 1952, when the question once more arose — this time in the State of Israel — the country’s chief rabbinate, under Rabbis Nissim and Unterman, based their opinion on that of the rabbis of Safed under Rabbi Shmuel Abbo and reconfirmed the ruling that the Bnei Israel are Jews for all purposes.

Rabbi Avraham Chaim continued constantly monitoring the implementation of the ruling regarding the Jewishness of the Bnei Israel in India. From time to time his father’s indigo business would afford him a visit and he would use the occasion to teach some Torah and advise the Bnei Israel on halachic matters. They felt great solidarity and respect for him. He was attached spiritually to his flock there, as they were to him, and his heart was always with them. At the same time, he raised funds for the enlargement of the Bar Yochai compound in Meron and added an iron door to the central building in order to prevent the villagers’ sheep from wandering in. His whole life was devoted to the community. He died during social service in India, he was buried there, and his grave became a holy place to many of India’s Jews.

![]()

French Patronage over the Jews of Galilee

The Jews of Safed at the beginning of the 19th century lived in misery and want. No one, including the government, had the power to defend them against attacks from their Arab neighbors. Rabbi Shmuel Abbo stepped in and requested that the Jews be allowed to arm themselves for defense. Obtaining no answer, he traveled to Algeria and, enlisting the support of the community’s leaders there, received the title of general consul for the Galilee. (According to other sources, he received the title through the aid of Sir Moses Montefiore during Montefiore’s first visit to Israel, in 1827.) Thus he received the legal right to defend the Jews of Safed and Tiberias in the name of France. In this capacity he accompanied Montefiore on his trip to Damascus in response to the famous 1840 blood libel.

His first act as consul was to gather the lion’s share of the Safed and Tiberias Jewish communities under the protection of the French government, by registering them as subjects. As foreign subjects they were accorded extra privileges, and the Abbo house quickly became a refuge for all the harassed and persecuted, regardless of religion and nationality. The Ottoman authorities never dared enter, because of diplomatic immunity.

Rabbi Shmuel was notably courageous, and not to be cowed by threats from Arabs who sought violence. He chased away from Safed more than a few bandits who had terrorized the vicinity, and once he even brought a firman (an official authorization) from Istanbul for the hanging of a notorious, murderous bandit who had held the Jews of Safed in fear. The order was carried out.

![]()

The Great Safed Earthquake

On January 1, 1837, Safed experienced one of the most severe earthquakes the Land of Israel had ever known. Almost the whole town was wrecked. Among the few houses unharmed was that of Rabbi Shmuel ben Avraham Abbo, and he considered Providence was responsible. Immediately he began efforts to restore the town. Together with the head of the Ashkenazic hassidim, the Rabbi of Avritch, he brought construction workers from Damascus to repair the buildings. They even rebuilt the Ari’s synagogue in the Sephardic quarter, which had previously looked like little more than a small cave. Rabbi Shmuel saw to it that life returned to Safed, and he was one of the town’s important leaders, as president of the kollel (religious school for adults) and as chief rabbi.

[1]

Surprisingly, an old friendship with Emir Abdel Kader, from Rabbi Shmuel Abbo’s youth in Algeria, bore new fruit as they met again in Israel:

After the revolt in Algeria was suppressed, Abdel Kader was exiled from France and he chose to live in Damascus. The renewed proximity of his old friend was of great value to Rabbi Shmuel Abbo in redeeming land in the Galilee and in the Hula Valley, for indeed — decades before the well-known pioneering Zionist settlements in Israel — Shmuel Abbo was laying the first foundations for Jewish agricultural settlement. And this was a private initiative, without community funding, arising from a deep religious-nationalist consciousness that our people cannot be redeemed unless the land is.

See also “The Abbo Family and the Emir,” by Yitzhak Ziv-Av, in Ma’ariv.

The Start of the Bar-Yochai Celebration

and the Jewish settlement in Meron

As far back as the first half of the 19th century, a few years after arriving in Israel, Rabbi Shmuel Abbo purchased the site of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s grave in Meron and built the synagogue that still stands there today. He even bought some 1800 acres of agricultural land in Meron Village from the local peasants and encouraged dozens of Kurdish Jewish families to settle there. They divided their time between agriculture — olive orchards in particular — and evening study of the Torah and Kabbalah.

This settlement campaign predated by decades the Zionist pioneer settlements in the Land of Israel, and it was a wonder to the eyes of the local Arabs. In recognition of his efforts, the Safed community presented him a Torah scroll with his name, and on the eve of Lag B’Omer 1833, the scroll was brought from the Abbo home in Safed to the Bar Yochai synagogue in Meron. Thus began a special tradition that over time became an inseparable part of the religious folklore of the Galilee and later spread throughout Israel. A short time later, the first scroll donated by the Jews of Safed was replaced by a scroll decorated in silver and gold, donated by the rabbi and consul Yitzhak Mordechai, and this is the scroll paraded until today in the festive procession from the Abbo home to the tomb of Bar Yochai in Meron on Lag B’Omer. And the torch passed from father to son – for five generations now – and each bearer of the flame adds a page to the impressive folk saga that is the ABBO STORY.

Yoseph Abbo Evron, in the decorated vehicle that brings the Torah scroll to Meron

Rabbi Shmuel Abbo served as chief rabbi and consul in the Galilee for more than forty years. He died in 1879, rich in years and accomplishments. His rabbinical and consular posts devolved to his son, Yaakov Chai.

THE SECOND GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RABBI YAAKOV CHAI ABBO

Yaakov Chai, second in the generations of the Abbo dynasty in Israel, was born in Safed in 1842 and would carry on in the footsteps of his father, Rabbi Shmuel Abbo, both as chief rabbi and as French consul in the Galilee, and above all in keeping and strengthening the tradition of the Lag B’Omer celebration at the Abbo home in Safed.

Yaakov Chai, second in the generations of the Abbo dynasty in Israel, was born in Safed in 1842 and would carry on in the footsteps of his father, Rabbi Shmuel Abbo, both as chief rabbi and as French consul in the Galilee, and above all in keeping and strengthening the tradition of the Lag B’Omer celebration at the Abbo home in Safed.

He became a rabbi and also helped his father manage the consular and large-scale business affairs, including redemption of land in the vicinity. He married Esther Malka, the daughter of Rabbi Yitzhak Cohen of Liverpool and granddaughter of Naftali Cohen-Tseddek. She had come with her parents to visit the Land of Israel and was only fifteen. In time their son, Rabbi Meir Abbo, would recount to Galilee-born journalist Aharon Even-Chen of Ma’ariv how the young Sephardic rabbi from Safed noticed the English tourist and fell in love at first sight:

THE ROMANCE OF THE LIVERPOOL RABBI’S DAUGHTER

AND THE SON OF THE RABBI CONSUL FROM SAFED

“One day in the early 1870s, my grandfather saw a caravan of camels proceeding along the street, and riding the camels were tourists in European dress. While he was looking with curiosity at the image passing before his gate, one of the camels suddenly bucked, and down from its hump tumbled a pretty young lady. We carried her into the house to recover, and at that time we learned that the tourists were none other than the family of the chief rabbi of Liverpool, who was strongly Zionist. The group — including the rabbi, his wife, their two daughters, and a number of friends from England as well — had arrived by ship at the harbor of Acre and were received there by the town’s British consul, Señor Avraham Finzi, who hired camels for them, and the first stop on their journey was the holy city of Safed.

“The Liverpool rabbi’s family stayed for a number of days in the home of Shmuel Abbo, and the girl so pleased him that he promptly asked her hand on behalf of his son. The parents — impressed by the courtly hospitality of the Abbo family and their love of the Holy Land — agreed to the match, and Esther Malka Cohen-Tseddek of Liverpool married the young Sephardic rabbi, wrapped her head in the Sephardic yazma according to the custom of that time, and adopted the local practices. Her young sister, Golda, married the British consul for Acre, Avraham Finzi, who was known for his heroism and greatly respected by the local Arabs. When he died, his young widow moved to Safed and lived on there into old age. As an octogenarian, she received the first British High Commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, when he came to vacation in Safed with his family. She rested her hand on his head and gave him the priestly blessing in English, and she even presented him with an unusual gift: a class photo from Liverpool, showing her and his father seated side by side, students at the same school…”

)Ma’ariv — “Yamim v’Leilot / Days and Nights,” 3.VI.76 )

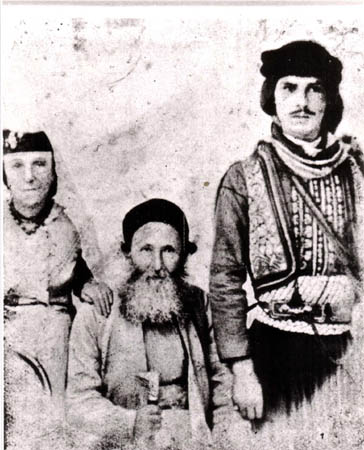

Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo continued in the footsteps of his father, as a redeemer of lands and a patron of the Galilee settlements. In any time of trouble for the Jews, the rabbi/consul could be seen in his uniform as he walked toward the government house or rode toward the district headquarters in Acre with two armed criers to clear his way. The capitulationist regime afforded foreign consuls great influence during Ottoman rule, and Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo turned this influence to the benefit of the Jewish community. His name is on the purchase of most of the land that was bought for settlements in the Upper Galilee, since ordinary foreign subjects could not buy land. He enlarged on the campaign that his father had begun in Meron by purchasing half the land of the village and establishing the first Jewish settlement in that area.

The Founding of Rosh Pina

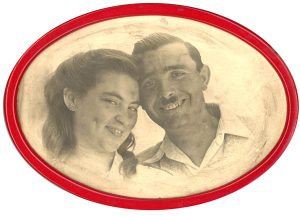

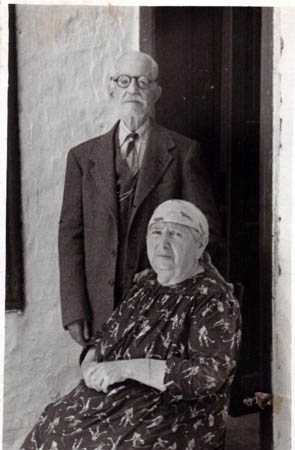

Rabbi and Consul Yaakov Chai and his wife Esther Malka. To his right, the bodyguard – “kawas” in Turkish

In the year 5642 (1881–1882), Rabbi and Consul Yaakov Chai Abbo helped David Shuv, one of the primary founders of Rosh Pina, to buy land. He was named honorary president of the first council while his brother Yitzhak Mordechai was named an “esteemed member” of the council.

The first of Tevet 5643 (1883) appears in the records of the town of Rosh Pina as the day the young settlement was saved from destruction thanks to the Rabbi and Consul from Safed.

That morning, the settlers were plowing. These were the first furrows in the community’s earth and the enthusiasm was boundless. Around noon, they were about to celebrate the marriage of a young couple who, in a lottery, had won one of the first homes. While the festivities were still under preparation, an accidental shot from the pistol of one of the young people hit an Arab builder from Safed, killing him on the spot. Immediately the news took wing and a crowd of excited Arabs from Safed, armed with clubs and knives, began mounting the hill and crying for revenge, for the destruction of the Jewish settlement and extermination of the settlers. The sheikh of Ja’uni, the neighboring village, quickly summoned his villagers and led by Haj Ali Jilboud, they stood as a barrier protecting the Jews with their own bodies. Meanwhile, David Shuv sent a young man named Zipris riding off to Safed to tell the French consul, Yaakov Chai Abbo, what was happening and request his help. The consul came immediately, with his two brothers Avraham Chaim and Yitzhak Mordechai, accompanied by guards from the consulate and a military detachment. They dispersed the attackers, took up the body of the victim, and arrested the young man who was accused of the shooting. Gradually calm returned, and the peasants from Ja’uni, not allowing the marriage to be halted, joined their Jewish neighbors in a night-long celebration.

Consul Abbo gathered the victim’s relatives and reached an agreement with them on a “suspension of hostility.”

Eventually, with the help of Baron Benjamin (Edmund) Rothschild and with the payment of compensation and a proper sulha, peace was achieved between the two camps and the settlement’s life returned to normal.

At great effort, in the year 5643 (1882–83) Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo and his brother bought the land for the settlement of Yesud HaMaalah, to be populated by immigrants from Mesrich; and in 5650 (1889–90) for Mishmar HaYarden, to be populated by immigrants from Poland and Germany. Later they stood by the settlers in times of trouble and hardship. Great tracts of land in the family’s possession were sold to the Baron’s administration for Jewish settlement.

The Abbo Family Lays the Foundations

for Settlement in Yesod HaMaalah and Mishmar HaYarden

The redemption of the land of the fertile Hula Valley and of the flat land along the Jordan southeast of the Bnot Yaakov Bridge, where Mishmar HaYarden and Yesud HaMaalah were built, was made possible by the praiseworthy initiative of the Abbo family and was achieved while Rabbi Shmuel Abbo was still alive, thanks largely to the complete trust with which the local Arab villagers viewed the family. In the book Pioneers of the Hula (p. 11), A.M. Harisman tells of the background leading to the purchase:

“At that time, the peasants — and particularly the Bedouin cultivating the earth of the Holy Land — had no title over their lands. They had squatter’s rights on the land handed down from their ancestors, who had been there since the territory was up for grabs. Then one day the Turkish government ordered a governmental registration of land according to owner. The Bedouin saw the order as a baleful one, and they balked at it, fearing that land registration was a trick to be followed by military registration. (Up to then, they had been exempt from the military draft.) Moreover, there was a loss of funds involved because of the registration fee. Meanwhile, in Safed there were three brothers from the prestigious Sephardic family Abbo: Rabbis Avraham Chaim, Yaakov Chai, and Yitzhak Mordechai. Their father, Rabbi Shmuel Abbo, was the French government’s consul in Safed … and these people were respected by the government and by the local Arabs. The Bedouin, who sought a way to escape the baleful order, asked the Abbo brothers of Safed to become partners with them as landholders in the territory of “Izbad,” thus rescuing the Bedouin from their straits and protecting them from the government … The Abbo brothers agreed to the deal: They gave the Bedouin money, paid the government’s fee, and registered the land in their name. Thus the Bedouin were saved, and the Abbo brothers became the holders of the land.”

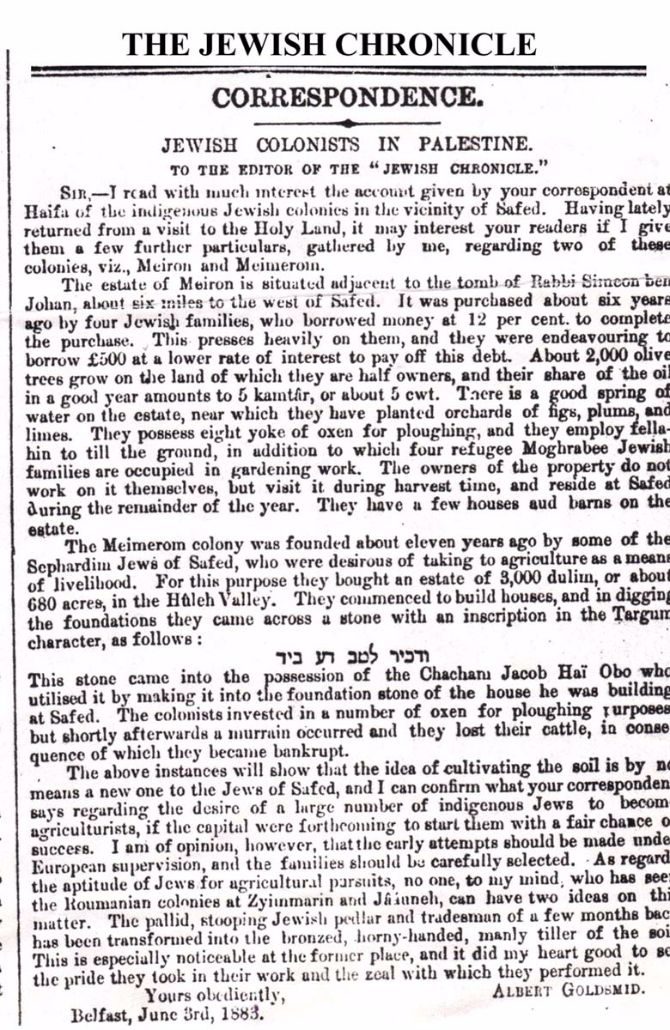

Mei Merom — Predecessor of Yesud HaMaalah

On the land that had been purchased, Yaakov Chai Abbo and the brothers Shlomo and Shaul Mizrachi erected a “colony” with the name Mei Merom by the shore of Lake Hula. Thus in 1872, eleven years before the birth of Yesud HaMaalah and ten years before Rosh Pina, the Abbo family laid the foundation for Jewish settlement in the Galilee and in the Hula Valley. A Jewish officer from England, Albert Goldschmidt, visited Safed in 1883 and wrote in his memoirs: “The colony of Mei Merom was founded eleven years ago by some Sephardic Jews from Safed, who agreed to support themselves with agriculture and to that end purchased 680 acres and built their homes.”

On the land that had been purchased, Yaakov Chai Abbo and the brothers Shlomo and Shaul Mizrachi erected a “colony” with the name Mei Merom by the shore of Lake Hula. Thus in 1872, eleven years before the birth of Yesud HaMaalah and ten years before Rosh Pina, the Abbo family laid the foundation for Jewish settlement in the Galilee and in the Hula Valley. A Jewish officer from England, Albert Goldschmidt, visited Safed in 1883 and wrote in his memoirs: “The colony of Mei Merom was founded eleven years ago by some Sephardic Jews from Safed, who agreed to support themselves with agriculture and to that end purchased 680 acres and built their homes.”

Some ten years later, Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo transferred some 600 acres of that land to the Mesrich immigrants who founded Yesud HaMaalah and gave them all possible further assistance.

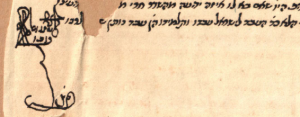

Moreover, in order to express his support and his faith in the future of the settlement, he formed a family tie with one of the settler pioneers, marrying his only daughter, Masouda, to Mordechai Lubovsky. At the time of the signing of the agreement between the Abbo family and the Mesrich immigrants, while the buyers were still milling around their potential properly, suddenly diggers discovered a stone with Aramaic writing saying “May all who dwell here be remembered with favor.”[2] Evidently more than anything else, this stone, which seems later to have found its way to a Paris museum, convinced the Mesrich immigrants to make the purchase.

In the picture: The Jewish Chronicle for an article on the colony at Yesud HaMaalah, from the year 1883.

The beginning of the village of Mishmar HaYarden is also connected with the Abbo family, and with the village of Meron at the foot of the Jarmaq. As Aharon Ever-Hadani relates in his book Mishmar HaYarden:

“The land for Mishmar HaYarden belonged to Meron village, at the foot of the beautiful, historic Jarmaq hill, and the Arabs from Meron village would go down at the start of winter with animals and seeds to plow their distant fields, like the Arabs of the other hill villages who would go down to plow in the valley. They would live in the caves that today are still there among the rocks, left from the days of the Canaanites and the Jews. They would return to the village after finishing the sowing, and go back down to harvest. The problem with this practice was that the neighboring Bedouin would make trouble in the villagers’ absence, ruining the fields with their flocks while there was no one to impede them. This was the situation throughout the flatlands, including of course the Mishmar HaYarden land. Malaria also took its toll, killing many of the peasants because they did not know how to maintain their health in this climate. Accordingly, the peasants sold their land, including rights over it, to Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo, of Safed, who served as French consul there.”

In September 1884 Mordechai Lubovsky arrived in Israel, the first Jewish immigrant from the USA, with the intent of buying land to settle on. The wild, primitive landscape around the Bnot Yaakov Bridge captivated him and he decided on the spot that this was the place he dreamed of. From Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo he purchased five hundred acres traversed by the bridge road, and he called the place “Shoshanat HaYarden.”

It seems that he wanted to set up an American-style cattle ranch, but after two years of failed attempts, he abandoned the idea and settled in Yesud HaMaalah.

Some years later, in 1890, he sold most of the land — 450 acres — to the Jewish Colonization Association. The deal was struck at the initiative of David Shuv, one of the founders of Rosh Pina, who divided the area into small units and settled agricultural laborers from Safed there. Since then, the place has been called Mishmar HaYarden.

The abandonment of Shoshanat HaYarden saddened Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo, who had spared no efforts in helping Lubovsky maintain himself there. Abbo refused to reconcile himself to despair in a place intended to become a thriving Jewish community, where instead shepherds and Bedouin were trespassing with their flocks and wiping out the new vegetation. David Shuv’s intervention and his attempt to revive the community with the help of the Jewish Colonization Association were doubtless influenced by the attitude of his friend Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo.

Some years later, Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo was injured in an accident and did not recover. He died at his home in Safed on the third of Tevet 5660 (December 1899), at the age of 58, in the midst of his praiseworthy public activism. He left two sons, Meir and Moshe; and a daughter, Masouda.

Safed and the other Galilee towns mourned. For more than twenty years, Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo had served as consul and as head of the community, demonstrating nobility and leadership, and he was loved and respected by Jews, Arabs, and Christians.

His death marked the end of a glorious chapter in the proto-Zionist Jewish settlement of the Galilee. He and his father (Rabbi Shmuel) were the pioneers who laid the foundations for Jewish settlement in the region, but the passing of those two giants was not the end of the Abbo family’s contribution to land redemption or to other important national goals. Shortly after Yaakov’s death, his son Meir would play a crucial role in saving Mishmar HaYarden from a caprice of the Baron’s clerk, who wished to take the farmers’ lands from them.

See also “The Abbo Family and the Emir,” by Yitzhak Ziv-Av, in Ma’ariv.

THE THIRD CONSUL FROM THE ABBO FAMILY

RABBI YITZHAK MORDECHAI

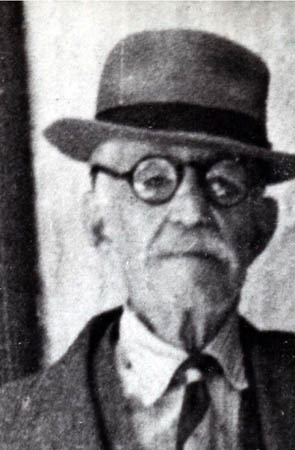

Yitzhak Mordechai Abbo

When Yaakov Chai Abbo died, his son Meir would have filled his place as consul, just as his father and grandfather had filled the position. However, because Meir was so young, the position passed to his father’s brother Yitzhak Mordechai, who held it until the First World War.

Like his brother the rabbi and consul Yaakov Chai, Yitzhak Mordechai continued in a broad defense of the rights of Safed’s people and of the Galilee’s Jewish settlements. He concerned himself particularly with the material and religious needs of the Meron farmers, and when after the death of Yaakov Chai Abbo the Ottoman authorities tried to take over the land from its residents, the consul Yitzhak Mordechai and his brother’s widow Esther Malka came to their aid and made clear that the lands of Meron belonged to the Abbo family, who enjoyed French diplomatic immunity. Then the authorities were deterred and their scheme went unimplemented.

He was a proud and observant Jew and fought zealously against the Catholic missionaries who made great efforts to secure converts. He helped restore the synagogue named for Yoseph Banaa (the White Tsaddik), which today still stands in the same location, and he contributed much funding for Safed community needs.

One important contribution of his was a Torah scroll decorated in silver and gold for the traditional Lag B’Omer Eve procession from the Abbo home to the Bar Yochai tomb in Meron.

This scroll, with his name emblazoned on it in silver letters, is still the one ceremonially carried from the Abbo home to Meron during the festivities.

The son of Rabbi Yitzhak Mordechai Abbo, named after his uncle Yaakov Chai Abbo, holding the Torah scroll that his father donated.

He was widowed twice: Sara, his first wife, died shortly after giving birth to their daughter Mazal. His second wife, Nechama, gave him two daughters and a son: Chana, Simcha, and Meir. Three years after Meir’s birth, she died. His third wife, Masouda, bore him a child for his old age and they named him after his uncle Yaakov Chai. Two years later, Yitzhak Mordechai died rich in years and in accomplishment, aged 79.

Yitzhak Mordechai’s son Yaakov Chai was born in 1917 and orphaned of his father at the age of two. During the Second World War he served in the French army and fell into German captivity. After the war he headed the Jewish community in Corsica. There he took a wife, Claire, who bore him two daughters and a son — Helene, Leah, and (after his father) Yitzhak Mordechai. He regularly attends the annual Lag B’Omer Eve celebration at the Abbo home and participates in the Torah scroll procession to Meron, in the tradition of his ancestors.

Yaakov Chai (center) with Yehudit Abbo Evron to his left and to his right the French consul from Haifa and the consul’s wife.

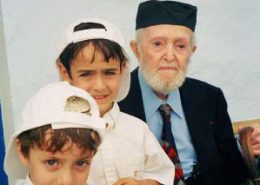

Yaakov Chai Abbo, third generation, and the sons of Rafi Ben Zvi Abbo representing the seventh generation.

![]()

THE THIRD GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

MEIR ABBO

Meir Abbo was born in Safed on the first of Tishrei 5631 (1870), to Yaakov Chai and Esther Malka bat Yitzhak Cohen, the granddaughter of Rabbi Naftali Cohen-Tseddek of Liverpool. He studied at a Cheder in Safed and later at the Tiferet Yisrael school in Beirut, run by Rabbi Zaki Cohen. It was a high school that also taught Judaism. With the aid of the consul Michael Goldsmith, who was a friend of his mother’s family in England, Meir was accepted to the Polytechnic School in England, where another student was the son of King Edward VII of England. On the day in 1910 when his schoolmate ascended to the throne in 1910 as George V, Meir sent him a congratulatory telegram and the king replied with a warm note that was later to rescue Meir from a wicked plot.

Meir Abbo was born in Safed on the first of Tishrei 5631 (1870), to Yaakov Chai and Esther Malka bat Yitzhak Cohen, the granddaughter of Rabbi Naftali Cohen-Tseddek of Liverpool. He studied at a Cheder in Safed and later at the Tiferet Yisrael school in Beirut, run by Rabbi Zaki Cohen. It was a high school that also taught Judaism. With the aid of the consul Michael Goldsmith, who was a friend of his mother’s family in England, Meir was accepted to the Polytechnic School in England, where another student was the son of King Edward VII of England. On the day in 1910 when his schoolmate ascended to the throne in 1910 as George V, Meir sent him a congratulatory telegram and the king replied with a warm note that was later to rescue Meir from a wicked plot.

When Meir returned from England to Safed, he worked as a secretary in the French consulate headed by his father. He knew Arabic and he established friendly relations with Arab notables and with high government officials, but he also knew how to stand firm in defense of Jews and Judaism. In 1898, he forcibly removed from the home of the Mufti of Safed a Jewish girl whom Arabs had kidnapped and were trying to convert. He also foiled various efforts of Christian missionaries among the Jews.

When Yaakov Chai Abbo died, his son Meir would have succeeded him as consul (the post held by his father and grandfather), but because of his youth the post passed to his father’s brother Yitzhak Mordechai, who held it until the First World War.

Even though the diplomatic post had passed to his uncle, Meir served as the head of the family for all other purposes. He inherited the historic family home, continued to live there, and scrupulously maintained the Lag B’Omer tradition: every year on Lag B’Omer Eve the festive procession set out for Meron bearing the Torah scroll, with ceremony and in great numbers.

Segal’s traditional klezmer band, in the square by the Abbo home, before the founding of the State.

Meir had inherited leadership ability, and he was highly involved in public matters with no thought of personal aggrandizement. He headed the Safed rabbinical court and served many years on the town council (which was composed mostly of Muslim representatives, with Jews as an insignificant minority). Like his fathers, he was sought out by his contemporaries in times of crisis, and more than once he risked his own life in order to save other Jews. Some of the incidents have the ring of legends today. For example, in 1912 an Alexandrian Jew who happened to visit Safed was arrested on suspicion of espionage and Meir snatched him from a certain death.

It happened thus: Having suffered defeat in their war against Italy, the Turks in every part of their empire were psychotically hunting spies. A Jew from Alexandria who lodged for a night at a hostel in Safed let out a few blunt and drunken sentences regarding the oppressive rule of the Turks. The same night, he was arrested and jailed. The owner of the hostel hurried to tell Meir Abbo, and though it was a stormy winter night, Meir immediately set out for the home of the governor.

Here is the account from his own diary:

“I knocked and entered. My friend welcomed me but did not disguise his surprise. What brought me to him so late at night through the pouring rain? When he heard what the matter was, his face paled and he told me to cease my involvement before (heaven forbid) it came to touch on me personally. … I returned home in defeat and sadness, having failed to save this poor Jew, and sleep was refused to my eyes.”

The same night Meir made another attempt, this time through another friend, the chief of police. After much pleading, he won permission to see the prisoner in private. And here Meir found a surprise, as he writes in his diary:

“I looked in his face, and it was none other than Nissim Mizrachi, a schoolmate from Tiferet Yisrael in Beirut and son of the famous grandee Yehuda Mizrachi of Alexandria.”

An exhausting campaign got under way to save the well-born young Jew. After much lobbying, Meir managed to bail him out and bring him to the Abbo home. But after a week, an order arrived summoning the suspect to Acre for a court martial, which in those days could only mean hanging.

Though it seemed that no more hope remained for the poor man, Meir Abbo learned by chance that the governor in Acre, Farid Pasha, was related to Emir Abdel Kader of Algeria, who had a history of friendship with the Abbo family. Immediately he telegraphed a relative of the Emir: “I am in Acre and in trouble with the government. Please rush me a note from your uncle the Emir to the governor.”

The answer was not long in coming: “The letter from my uncle is sent, meeting and exceeding your wish. Call on me if you think it necessary and I will come personally to Acre (Emir Taher).”

The whole atmosphere changed as if magically: The governor received Meir Abbo with honors and personally undertook the young Jew’s questioning. In less than a day the truth was out and the youth from Alexandria, victim of a baseless charge, was free to return to his family, concluding the story of another rescue by the Abbo family.

A much more serious incident occurred in 1915, during the First World War.

Twelve men from notable families of the town were arrested for attempting to cross the border and volunteer for the French army. The entire group was charged with treason and faced execution. No one dared intervene on their behalf. Once more it was Meir Abbo who risked his life, traveling to Jerusalem in an attempt to save them. To their families he said, “Trust in God, and as for me, I shall either return with your sons or hang with them.” He reached the capital on Friday, after an exhausting mule ride, and he immediately headed for the jail. When the condemned men saw him, they shouted out “Here is Elijah the Prophet, come to save us!”

All Saturday he went from one official to another, exerting all his influence, neither resting nor staying silent until he managed to redeem the prisoners and bring them safe back to their families, who greeted him with hugs, kisses, and songs of thanks. Safed was overjoyed.[3]

The Abbo Home in Safed as a Shelter

for Illegal Immigrants in the 1930s

The Abbo home was always a shelter and a lodging for anyone oppressed or persecuted by tyrannical foreign rule — regardless of race or religion. In the early 1930s the home became a way station for Jewish immigrants who were considered illegal by the British. All the family was active: Meir’s son, Raphael, would take the immigrants on foot across the northern border, by paths that were scarcely paths. A song from later years spoke fittingly of “nights of darkened stars,” though the illegal immigration then was the one organized by the Palmach.[4]

The father, Meir, gave them shelter and clothing (since they generally fled in from Syria unclothed and penniless) and even saw to appropriate papers for them. Thanks to his close connections with an Arab who was a longtime government worker and had issued birth certificates for the Ottomans, he managed to obtain the original stamps from those days and with them he prepared documents attesting that the new immigrants had been born in the Holy Land.

After two years or so, the British, tipped off by an informer, decided to make a surprise search of the Abbo house. On the afternoon of January 24, 1935, British investigators, reinforced by police, knocked at the gate. The place was searched thoroughly. In the body of an old oil lamp, stamps were hidden that had been used in falsifying birth certificates for the immigrants. The chief inspector was about to look into the lamp when suddenly a sheet of paper, yellow with age, fell out of it. The officer spread it out and looked it over in hypnotized curiosity, fixated all the time on the British royal emblem at the top. It was King George’s reply to the congratulations of his schoolmate Meir Abbo on his ascension to the throne.

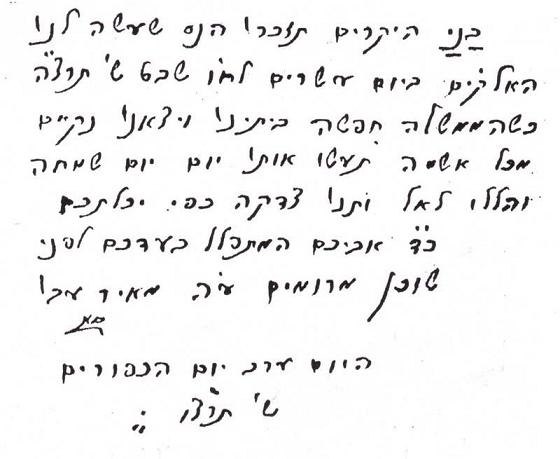

“Dear With measured care, almost with servility, the inspector refolded the note and replaced it in the lamp without further searching. Then he turned to Meir Abbo and said apologetically, “Mister Abbo, I ask your forgiveness. No doubt a terrible mistake has been made…” He assembled his men and left the place. For a long moment, the family was speechless at the miracle they had just witnessed, and Meir Abbo wrote personally inside the cover of his prayer book:

“Dear With measured care, almost with servility, the inspector refolded the note and replaced it in the lamp without further searching. Then he turned to Meir Abbo and said apologetically, “Mister Abbo, I ask your forgiveness. No doubt a terrible mistake has been made…” He assembled his men and left the place. For a long moment, the family was speechless at the miracle they had just witnessed, and Meir Abbo wrote personally inside the cover of his prayer book:

children, remember the miracle that the Lord wrought for us on the twentieth of Shvat, 5695, when the government searched our house and we were spared all accusation. Make of that day a day of rejoicing, praise Heaven, and give charity to the extent to your ability. So requests your father, who prays for you before the Almighty. Signed, Meir Abbo.”

The Saving of Mishmar HaYarden

from the Corrupt Clerk of the Baron

Encouraging settlement in the Galilee was central to the Abbo family’s activities during three successive generations, and Meir is included. An instructive example comes from 1903. This is a little-known story. From the records of the late Meir Abbo the following picture emerges:

When Lubovsky transferred the lands of Shoshanat HaYarden to the Jewish Colonization Association in 1900 through David Shuv, ownership was temporarily registered for some reason — perhaps in order to eliminate a bureaucratic delay — in the name of the Baron’s clerk.

The Baron dismissed his clerk in 1903, and in Beirut the clerk, a man named Ossovitsky, claimed to the governor that the lands of Mishmar HaYarden were his personal property, so were the buildings there, and the farmers were trespassers who must be evicted. To strengthen his claim, he brought the deed of sale bearing his name.

The governor, who was a friend of Ossovitsky, accepted the claim and ordered the farmers evicted. The local governor in Safed at the time, Hashem al-Atassi (later to be president of Syria), was ordered to carry out the decree and although unhappy with it, had no power to object. The Baron’s new clerk for the Galilee, Saporta, was also consternated and helpless. He hurried to Safed to confer with Meir Abbo in hopes of finding a way out. After weighing and exploring the problem, they concluded that since the tracts were still shown in the land registry as property of the Abbo family, the Abbo heirs could claim ownership. In order to give the claim authority, the whole Abbo family went out to settle in Mishmar HaYarden and populate all the abandoned houses there. They stayed there many weeks, making it known that they would not move from the place and were prepared to take up arms to defend their rights. Since they were well-connected French subjects, the authorities hesitated to evict them by force, and al-Atassi the governor of Safed, who was reluctant from the outset regarding the eviction order, did not exert himself particularly to carry it out. He would arrive time after time leading his troops, threaten eviction in the name of the law, and brandish the eviction order. In response, the family would brandish the French flag and threaten to fire on any trespassers. After an exchange of hard words, the Turks would leave until next time.

In the end the French ambassador in Istanbul intervened, in response to an appeal from Esther Malka, the widow of the consul Yaakov Chai Abbo. Prompted by the ambassador, the Foreign Ministry of Turkey instructed the governor in Damascus to stop all actions against the residents of Mishmar HaYarden until the Ossovitsky matter could be clarified in court. The eviction order was cancelled, and the village of Mishmar HaYarden, which had almost been stricken from the map, was saved. The farmers returned to their homes. Two months afterward, Ossovitsky reached a compromise with Saporta and the Jewish Colonization Association was registered as legal owner of the land.

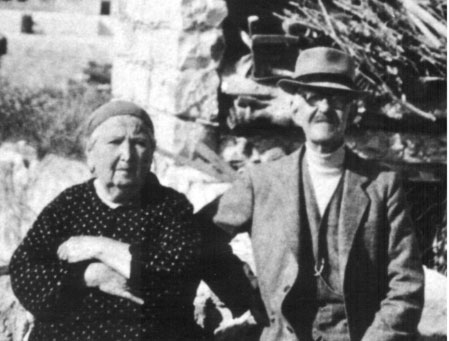

Meir died at home in Safed on November 23, 1947, seventy-seven years old, a few days before the UN resolution recommending the establishment of the State of Israel. His death ended another important chapter in the Abbo family’s history of land redemption and the encouragement of settlement in the Galilee. (Thousands of dunams of land in Meron were still registered to the family, and before his death, he transferred them to the Jewish National Fund for a nominal price.) Meir bridged two regimes, the Ottoman and the British. Death was granted to him swiftly, without suffering. A relative passing by the house at the time saw him slumped over a letter, the pen still in his hand. He had been writing to his daughter in America. The relative closed Meir’s eyes, said shema yisrael, and went to tell the family.

All his life he was accompanied faithfully by his Russian-born wife Rachel née Gladstone, who died a few months later. They had four daughters:

All his life he was accompanied faithfully by his Russian-born wife Rachel née Gladstone, who died a few months later. They had four daughters:

Julie, Golda, Margalit, and Esther; and one son, Raphael, who was to serve as head of the family, and of the dynasty, in the fourth generation.

THE FOURTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RAPHAEL ABBO

Raphael Abbo was born in Safed on November 29, 1899. His father was Meir Abbo and his mother was born Chaya Rachel Gladstone in Russia. She immigrated to the USA and thence in 1897, with her family, to Israel. Explaining his name, Raphael wrote in his diary: “Two weeks after my birth, my grandfather Rabbi Yaakov Chai Abbo died. He had been my godfather, held me in his soft hands, raised his eyes skyward, proclaimed, ‘Rephani hashem verapeh — Heal me, Lord, and I shall be healed,’ and accordingly named me Raphael.”

Raphael, a fourth-generation Abbo, was a heroic figure in his own right.

For decades he filled a central role in the civic and cultural life of the town of Safed, becoming an integral part of the townscape for all its populations, Jewish and Arab alike.

His talent for organization, his bravery, and his great physical strength made him the natural leader of the Jewish boys of the town and brought respect and admiration from the Arab neighbors as well. Throughout his life Raphael served as a living symbol of Israel’s national resurgence on its ancestral land. He is well described by the poet’s words “We are the last generation of slaves and the first of redemption.” He fought zealously for all the symbols of national rebirth — flag, anthem, language, songs, and the return to rural life. He decried the diaspora lifestyle of the previous generation and wanted to live the new life of a free people untrammeled by complexes from the past. All this found expression in his public and organizational work, which he kept up till the day of his death.

From boyhood, Raphael devoted most of his time to the defense of Safed. At eighteen, upon the conquest by Britain, he was among the first Jews appointed to the mandatory police. In 1921, after three stormy years of duty, during which he sustained a gunshot wound in his leg during a confrontation with Arab bandits, he left the police and, being a French subject, was able to gain admission as a cadet at the officers’ school in Beirut. In his memoirs he wrote, “After finishing my studies with distinction, I received my commission. My friends and commanders all predicted a bright future for me, should I continue in the military, but I missed the Land of Israel more than I sought that career, and I tendered my resignation to the French government.”

Returning to Safed, he embarked on public service with a particular emphasis on the advancement of sport among youth. To him, mens sana in corpore sano was not merely a slogan but a way of life. The opening of a branch of the Maccabi sports league was one milestone along the path to its fulfillment: “In 1925 I founded the Maccabi branch in Safed,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and over the years I organized its activities and held office as its head. Maccabi served us as a training ground for youth, and from among its ranks we enlisted the best and most trustworthy to the Hagana.” The safety of the Jews of Safed, who were an insignificant minority among a sea of Arabs, was always foremost in his thoughts. He founded an organization named “Association of Youth for Safed” in the early 1920s. More than once, his zeal for the national honor and his stormy temperament brought him into bitter conflict with the officers of the Hagana, who generally preferred a policy of restraint despite repeated Arab provocations.

Returning to Safed, he embarked on public service with a particular emphasis on the advancement of sport among youth. To him, mens sana in corpore sano was not merely a slogan but a way of life. The opening of a branch of the Maccabi sports league was one milestone along the path to its fulfillment: “In 1925 I founded the Maccabi branch in Safed,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and over the years I organized its activities and held office as its head. Maccabi served us as a training ground for youth, and from among its ranks we enlisted the best and most trustworthy to the Hagana.” The safety of the Jews of Safed, who were an insignificant minority among a sea of Arabs, was always foremost in his thoughts. He founded an organization named “Association of Youth for Safed” in the early 1920s. More than once, his zeal for the national honor and his stormy temperament brought him into bitter conflict with the officers of the Hagana, who generally preferred a policy of restraint despite repeated Arab provocations.

The riots of 1929 found Raphael at a position in the center of town. “It was the bullets of the few raining on the Arabs — despite the command for restraint — that turned back the first attack on the commercial center and on the Jewish quarter, saving them from extinction,” he wrote in his diary. Immediately afterward, he turned to rescue work: “Heading a small group of youngsters, I entered the old Jewish quarter, and under a shower of shots and with flames spreading around us, we brought the wounded out from collapsing ruins and led them to the hospital.”

Throughout that night he continued the evacuation — sometimes carrying the wounded on his back — to the government house, which was thought to afford British protection. Later, men of the Jordanian frontier force fired straight into a crowd of evacuees who had gathered there, wounding many.

The memory of the attacks would long remain with him, and the main lesson he drew was that foreign goodwill was no longer to be relied on, but instead a local nucleus of protection must be formed for self-defense. And thus in 1935 he founded the “Association of Hebrew Hunters,” which under cover of sporting and hunting activities assembled roughly a hundred Jewish boys and girls who would openly practice with weapons, bullets, and targets. Each member of the association was required to purchase a hunting rifle, generally automatic, and thus many Jewish families were armed legally.

The first test under fire for the association’s members was on Yom Kippur 1936, at the height of the attacks. There had long been a rumor in town that the Arabs were preparing to surprise the Jews on that holy day. (History would repeat itself thirty-six years later, in the Yom Kippur War of 1973.)

On Yom Kippur 1937, Raphael assembled the hunters and deployed them, armed with rifles, in all the synagogues — particularly those of the old Jewish quarter, which bordered the Arab neighborhoods. And indeed, as the Jews of Safed, who were fasting, arrived at the final Yom Kippur prayers, bullets rained on the synagogues. Upon Raphael’s command, the hunters returned heavy fire straight at the Arab quarter.

Quickly cries of woe were heard from there, and the firing stopped. The next day it was found that, uncharacteristically, all the wounded this time were on the Arab side. For many weeks there was silence from the rifles that had previously disturbed Safed’s Jewish quarter almost every night.

The same year, Arabs made an attempt on Raphael’s life while he was about to return by bus from Tiberias to Safed. A shower of bullets hit the bus. The driver panicked and almost stopped (which would have made a massacre unavoidable). Only thanks to the steady nerve of Raphael, whose courage was praised the next day in the newspapers, did the bus leave the ambush behind and reach Rosh Pina. While giving first aid to Avraham Mizrachi, a gravely wounded passenger, Raphael made the driver continue. Mizrachi died later of his wounds.

During the Second World War, the British mandate authorities appointed Raphael to lead civil defense in the Jewish quarter, while at the same time he was named enemy number one by the Arab street youths of Safed. After one grave incident in which he had to make his way through a crowd of Arab demonstrators (who were too astonished by his nerve to stop him) the Jerusalem newspaper Palestine forcefully demanded his expulsion from Safed and even made a point of publishing a picture of him. At the start of November 1947 there was a second assassination attempt, while Raphael was near the Arab quarter, next to the governmental office building. An unknown shooter fired a number of bullets at him but missed.

Raphael Abbo leading the Haga civil guard parade in Safed, 1949.

After the UN decision to partition the Land of Israel, Raphael was assigned to set up the “People’s Guard” ( “Mishmar Haam“) in Safed, which would become the nucleus of the later Haga civil guard. It was a job of creation ex nihilo: to build shelters, see to the reliable supply of ammunition, organize the elderly residents in military fashion, and more. He set himself to it and accomplished the impossible: an organized People’s Guard that would serve as a model for all the towns of the nation.

Till his final day he was in command of Haga in the northern district, with the rank of major, and he won many letters of commendation from his commanders. In his book In the Shadow of the Fortress, the commander of the People’s Guard during the siege of Safed, Meir Meibar (Meiberg), called Raphael “A man of courage and a proud Jew, one of the exemplary figures of the town, one of the Sephardic nobility, a man of authoritative, determined bearing. I could always rely on him”. After the founding of the State, he was appointed regional Haga commander, and he served in that position till the day he died.

Throughout the Mandate years, Raphael Abbo served as a government worker. With the founding of the State, he was put at the head of the Minorities Office in Safed, and a year later he was assigned to set up and head a branch of the Ministry of Finance in Safed.

In addition to all his public responsibilities, for sixteen years (until his death) Raphael scrupulously organized the Lag B’Omer celebration of the Abbo family, in every detail, with his wife Laura assisting him. During his time the ceremony took on, in addition to its public and national-religious aspects, an official aspect as well.

With the State of Israel established in his lifetime, Raphael was privileged to see the Torah procession from the Abbo home including, for the first time, presidents and ministers of the State of Israel. He had learned the national anthem and sang it proudly at every public occasion, and its words — a free people in our own land — became flesh and blood before his eyes.

Raphael Abbo died in Safed on February 7, 1964. With the news, great mourning descended on the town. One after another the shops closed, and the workshops fell silent. Everyone spontaneously set off to the funeral. Raphael’s Haga soldiers, accustomed to seeing him at the head of every parade, reported this time with no need for orders and walked with his coffin, heads lowered. A whole town came out to pay its last respects to one of its dearest sons.

His children from his first wife, Anna Virginia Mercedes, were the two sons Yoseph and Zvi; and from his second wife, Laura Harari, a daughter, Atzmona.

With his passing, the Lag B’Omer tradition descended to his eldest son, Yoseph.

THE FIFTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

Raphael left two sons, Yoseph and Zvi, and the tradition was intended to pass to them. He died suddenly, very close to Lag B’Omer, when Zvi the younger son was studying in the USA. The continuation of the tradition thus passed to the elder son Yoseph.

ZVI ABBO — FIGHTER AND EDUCATOR

צבי עבו ז”ל דור חמישי למסורת

The younger son of Virginia and Raphael Abbo, Zvi, was born in 1928. He was among the defenders of Safed during the siege in 1948, and one of the more courageous fighters. More than once he risked his life in order to turn back attacks on the Jewish quarter at one of the most dangerous and sensitive points. In his book In the Shadow of the Fortress, Meir Meivar, who was commander in Safed during the siege, praised the courage Zvi showed during one of the more difficult moments, when the Arabs almost managed to penetrate:

“Zvika Abbo, still a boy, who was accompanying the section commander, ran toward the enemy fire with a grenade in his hand and shouted, ‘It won’t happen! They won’t enter!’ and indeed by throwing that grenade, while exposing himself to the attacking enemy at the risk of his life, he halted the Arabs and the Jewish quarter was saved.”

After the liberation of Safed, Zvi fought under the IDF and was wounded in Operation Ten Plagues in the Negev.

After the war, he enrolled in the law school of Hebrew University in Jerusalem, passed the bar in 1956, returned to Safed, and worked some years in law. Like his father, Zvi was gifted with a strong civic sense, and during his years as a lawyer he founded a Franco-Israeli friendship association in Safed, as well as founding and heading a branch of the Junior Chambers of Commerce. In 1960 he was appointed vice president of the national office, and he traveled as its delegate to fifteen African countries to set up branches. On his return, he went to the USA for further study but found himself busier with education and with increasing Jewish and Zionist awareness among the Jewish community. He was appointed a lecturer in the Department of Judaic Studies at the University at Albany (New York State University), and he developed a new system for teaching Hebrew with the aid of television.

Zvi Abbo and his bride Sheila at their marriage in the USA, 1946.

In 1964 he married Sheila Rothschild, whom he had met in the USA. They had two daughters and a son — Meira, Michal, and Raphael (named after his father). In 1974 he was appointed head of the Department of Judaic Studies at the University at Albany.

Zvi returned to Israel in July 1975 with his family in order to make his home here. He immediately began wide-ranging activity on behalf of Safed, his ancestral home, with special emphasis on the old quarter. Even during the time of his father Raphael, he had aided in the development of the family’s Lag B’Omer tradition, and it is largely thanks to him that the ceremony took on its official aspect. Zvi hoped to restore Safed to its former glory, and he founded a national association for the purpose. But his work was cut short by a fatal traffic accident on March 11, 1976, on the way to Tel Aviv from Jerusalem, where he had been speaking to an audience of Jewish students from the USA.

His untimely death was a heavy blow to his family and to the town of Safed.

YOSEPH ABBO EVRON — CONTINUING THE TRADITION

IN THE FIFTH GENERATION

Yoseph & Yehudith Abbo Evron

Yoseph Abbo Evron, a writer and journalist from the fifth Abbo generation of Safed, has been continuing the Lag B’Omer tradition for the past forty years, since the death of Raphael his father.

Yoseph’s work as a journalist has struck many echoes. His political interviews in the 1960s on “Haboker” daily paper and in the weekly “New Look” (Mabath Hadash) have been extensively quoted in the Israeli and international media. He has also worked as a military writer, and his articles on air battles of the Six Day War won him a personal letter of commendation from air force headquarters.

In the years 1969–1991 he served as spokesman for the Israel Military Industries. He founded and edited its newsletter, B’Taas.

His books “On a Rainy Day” (published by Otpaz, 1969) and New Look at Suez (published by Modan, 1986) added an important historical layer to the research into the causes of the Suez Campaign. The books The Security Industry in Israel (Israel Ministry of Defense, 1980) and Shield and Spear (Israel Ministry of Defense, 1991) detail the history of military manufacturing in Israel and won him the Defense Ministry’s Industry Prize.

The book Gidi – The Campaign for Removing the British from the Land of Israel (Israel Ministry of Defense, 1980) throws new light on dramatic events of the underground period such as the King David Hotel bombing, the Acco prison break, the hanging of the sergeants, and more.

From his earliest youth he volunteered to serve the nation: in a platoon commander’s course with the Hagana (in Geva, 1944); as a guardsman in the Jewish settlement police (1945); and when the British Mandate authorities invaded Moshav Biria on 27 February 1946 and jailed its defenders, he led some 500 Gadna youths along hidden wadi paths under the noses of the British, straight to the occupied hill of Biria to set up a new position there. Later he joined the Palmach navy at Givat HaShlosha.

Late in 1946, when the Hebrew rebellion movement broke up, he left the Palmach and joined the IZL (Irgoun Zvai Leumi) in Tel Aviv. In 1947 he published an open letter to his Palmach friends, “Letter from a Soldier to a Soldier,” which brought an answer from the Hagana, followed by an “Answer to an Answer” from Menachem Begin, who described the letter as “The IZL’s best broadside.” (The whole episode is mentioned in Begin’s book In the Underground, vol 3 p. 40.) Afterward,he published a pamphlet called The Voice of Freedom, printed by stencil in 1947 by direct order of IZL commander Menachem Begin, who sent the author a personal letter of commendation.

Yoseph participated in various IZL operations, including intelligence operations under the direct command of “Gidi” (the code name of the IZL operations chief, Amichai Paglin).

As the War of Independence approached, he participated in battles for the conquest of Haifa (Wadi Nisnas) and the first IZL incursion into Ramla. When the IZL disbanded, he was one of Menachem Begin’s invitees for the founding meeting of the Herut movement.

In the framework of the Israel Defense Forces, he took part in the liberation of the Galilee, in the 11th Battalion (Oded Brigade), as a machine-gun sergeant. Subsequently he took part in Negev battles, including the conquest of Uja El-Hafeer (Nitzana) as a patrol sergeant in the 89th Mechanized Battalion (8th Brigade).

adfasdf

asdfasdf

In July 1949, while still in compulsory military service, he married Yehudit Kantarovitch – granddaughter of a founder of Rehovot, Nissan Kantarovitch .

They had met in the IZL.

They have two daughters, Aluma and Rephaella; and two grandsons, Zohar and Roni.

For 50 years Yoseph has been carrying on the family tradition with the help of his wife Yehudit. Every Lag B’Omer, like his forefathers, Yoseph scrupulously observes the commandment of bringing the family Torah scroll from the Abbo home in Safed to Meron in a festive procession. And in keeping with the tradition, he always invites representatives from the French Embassy in Israel. They bring the blessing of their government to the Abbo family, whose ancestors were their consular representatives in the Galilee for three successive generations.

The French ambassador, Alain Pierret, decorates Yoseph Abbo as a chevalier of the Legion of Honor on behalf of the President of France, in Safed town hall.

In 1987, French ambassador Alain Pierret surprised Yoseph by awarding him, in the name of French President François Mitterrand, the title “Chevalier of the Legion of Honor” “for conscientiously keeping and fostering the tradition and the friendly ties between Israel and France.”

Five years later, on Lag B’Omer Eve 2002, on the occasion of the festive departure of the Torah scroll from the Abbo home, Oded Hameiri, who was then the mayor of Safed, presented Yoseph Abbo Evron with a Certificate of honorary citizenship in Safed “for keeping the tradition and continuity.”

In 2013 LAG-BAOMER’S EVE, a special gift was bestowed on Yossef by the Mayor of Safed Mr. ILAN SHOHAT: a silver Jewish ‘SHOFAR’ (ram’s horn), a symbol of Yossef’s 50th anniversary =”YOVEL” in Hebrew) of holding ABBO’S tradition to his last day. With the passing away of Yossef at 2014, rich in years and in accomplishment, at the age of 89, ABBO’S tradition has been handed to lawyer RAPHAEL ABBO, the 6th generation, son of blessed_memory ZVI ABBO , Yossef`s brother

THE SIXTH GENERATION OF THE TRADITION

RAPHAEL ABBO

The younger son of Sheila and Zvi Abbo, was born in the USA, at 1970. Grew in Jerusalem

[1] A document remaining from that time says:

“My heart wails like the pipes, for more than two thousand souls are entombed beneath the walls of their own homes. My heart, my heart is with the victims. Synagogues and schools fell to the ground; so did the whole great school building that is named for the holy Maran, with more than ten thousand books inside, a precious collection honoring the religion and documenting the community. … Then up rose our rabbi and teacher Shmuel Abbo, God grant him long life, one of the remaining great students of nature and builders of the community, and his destiny was as no man’s before: the great earthquake had brought the city to the ground and homes, synagogues, and schools were destroyed, kings would not have believed that in a hundred years a community could be rebuilt in that city of God’s, but the rabbi, wise beyond his tender years, was touched with the spirit of God, undertook the role of savior at the risk of his life, his heart like the lion’s and his voice in the ears of kings, and he marshaled assistance from the community. Within a short time he built a number of synagogues and a number of schools, and working with all the strength God gave him, and with his own two hands, from underground he brought back to the light of day Torah scrolls and schoolbooks and commentaries and all the holy writings, may his merit protect us.

“I was in the Galilee at the time, and I have seen God’s works but this was a most memorable thing, and within a short time a proper city of Israel was built, a large city of scholars and of writers and of rabbis great in number and stature. This much will all be told.

“Thus may one see the awesome works of the everlastingly faithful Fount who chose the arm of Abraham…

(from History of Safed, by Natan Schor, p. 186)

[2] For more than a hundred years now, the stone has been an important item in the history of Yesud HaMaalah. When visiting the town, Israel’s late president Yitzhak Ben-Zvi looked for the stone. From there, he went up to the Abbo home in Safed, on the understanding that the stone had been brought there, and for several hours he searched the basement in vain. There are two theories: the stone went either to the Louvre or to the British Museum.

[3] After Meir Abbo’s death, his daughter Margalit recounted: “As Father was lying before us and psalms were being said for him, suddenly an old woman arrived. So bent over she was that she seemed to be crawling. … She approached the dead man, uncovered his face, brought her mouth to his ear, and shouted, “Meir Yitzhak! When you reach the throne of the Almighty, don’t forget to mention you saved twelve boys from hanging, and one was my son.”

[4] During the British mandate, the northern checkpoint and customs station was at the road crossing for Rosh Pina, Safed, and Tiberias. Laura Abbo, the wife of Raphael, recounts: “On an immigration night, my husband would organize a bus of young men and women from Safed, as if they were off to a dance in Yesud HaMaalah or in Metulla. They would pass in a great crowd through the customs station at Rosh Pina, and Raphael, who was well known to the policemen, would greet them and invite them to attend the big party. … And in fact on that night there would be a noisy ball at Yesud HaMaalah, and late in the night the partygoers would return exhausted and ‘drunk’ from their ‘revels.’ When the bus reached the customs station on its way to Safed, my husband would wave to the policemen and they would wave back, gesturing the driver through without bothering to check inside where new immigrants had taken the places of Safed’s veteran residents.